A brief history of the Cowper's

MARY COWPER 1760 -1841

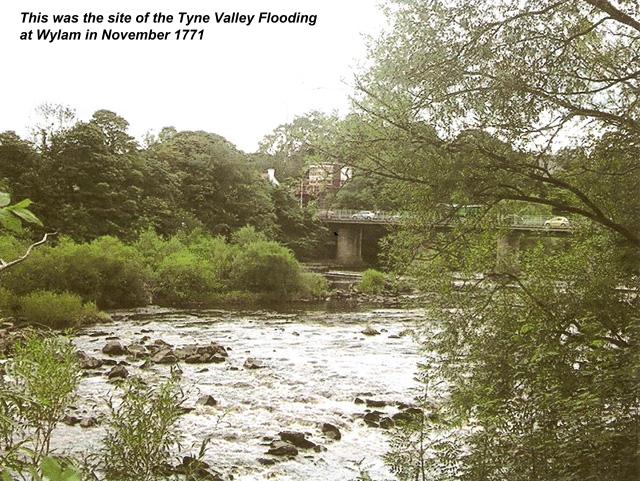

Up until 1st July 1837, a total of 43 found marriages occurred in Northumberland with the surname spelling of Cowper, with only 8 of the 43 found Cowper marriages occurring in the Northumberland area of Ovingham, with the remaining 35 probably being spread between Corbridge, Berwick, and Newcastle upon Tyne. The last entry for Ovingham, pre 1837, appears to have occurred on 7th May 1772. Six months previous, in the November of 1771, much of the Tyne Valley was flooded, killing many people in the area. At that time, there was no bridge to cross the river at Ovingham and locals were forced to use a ferry service operated by the Johnson family. Alas, as the river levels rose, the ferry boathouse became flooded, killing 11 people. Ovingham, for a while, became isolated from other villages, and the thought of any reoccurrence of the flooding forced many people to leave the area. This was probably the main reason for no more Cowper marriages in Ovingham after May 1772. Today, the ferry boathouse is home to The Boathouse Inn

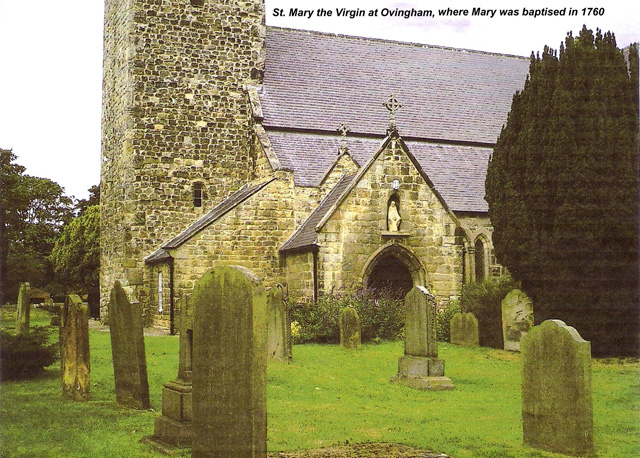

My x5 great-grandmother, Mary Cowper was born in Wylam in 1760 and was baptised in Ovingham on 24th March that year, the youngest of seven found offspring born to John and Elizabeth Cowper. The Tyne Valley flooding of 1771 appears to have had an effect on this family also, as by 1780 Mary was living in County Durham, at

My x5 great-grandmother, Mary Cowper was born in Wylam in 1760 and was baptised in Ovingham on 24th March that year, the youngest of seven found offspring born to John and Elizabeth Cowper. The Tyne Valley flooding of 1771 appears to have had an effect on this family also, as by 1780 Mary was living in County Durham, at

Brancepeth. It is not certain if all of Mary's siblings moved to County Durham, as marriages for at least two of the siblings may be found at Heddon-on-the-Wall, a short distance from Wylam. These marriages are dated 1771 and 1774. We know from records that Mary Cowper's family line had lived in and around the Ovingham area since at least 1683 and prior to that, were situated in Corbridge. Prior to the Corbridge connection, Newcastle upon Tyne appears to be the main area, possibly dating back to at least 1575, but this is unclear at present. What occupations the Cowper's had in Corbridge and Wylam is open to speculation, but one of the main industries in the former, especially at Corbridge Fell at Dilston, certainly in the 1700s was wood, so it seems logical to suggest that, at some point, the Cowper's were Woodmen. However, given their movements over the years and the areas they inhabited, it would also be fair to suggest that they were quite possibly involved in farming. When Mary Cowper married Peter Pearson at Brancepeth in 1781, the latter was employed as a Joiner, but his and Mary's descendants were also involved in farming around 1810 until about 1930, so maybe a pattern had formed through Mary's side of the family line.

When the Cowper family members lived at Heddon-on-the-wall in the late 1700s, the area was mainly industrial, with collieries here and there. The village itself lay 9 miles west of Newcastle upon Tyne and stood on the site of the Roman Wall from which it takes part of its name. Heddon means 'Hill where heather grew', and indicates that the area was once moor land and a part of the Roman Wall is still visible as you drive towards Heddon via Throckley main street. At the southeast end of the village is a row of cottages known as Frenchman's Row, originally built in the late 1700s to accommodate colliery workers, but in 1799 these cottages were used for another purpose. Following the French Revolution, any priest who refused to take an oath which was different to the belief of his own church, was forced to leave France. As a result, thousands of priests and nuns fled to England, where a number of them found refuge in Heddon, occupying the then empty cottages. These buildings were demolished in 1960 and replaced by a new row of cottages.

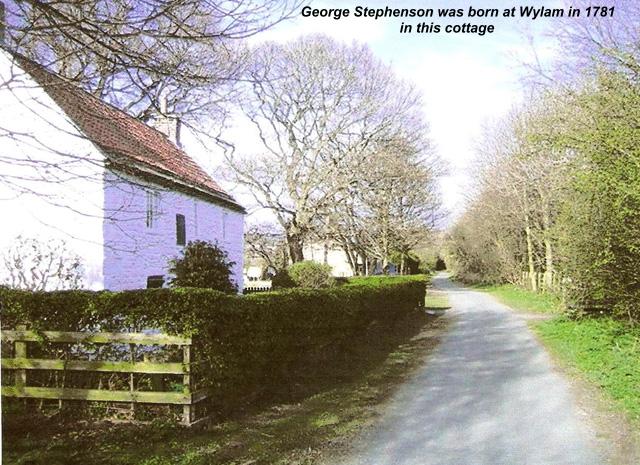

Ovingham was formerly a market town, and today is a very attractive country scene, similar to parts of Harrington High Street in Cumbria. In the mid 19th Century, Ovingham was a parish comprising the townships of Dukeshagg, Eltringham, Harlow hill, Hedley, Hedley-Woodside, Horsley, Mickley, Nafferton, Ovingham, Ovington, Prudhoe, Prudhoe Castle, Rouchester, Spittle, Welton, Whittle, and Wylam. On its boundary lay Stamfordham, Heddon-on-the-wall, and Bywell St. Andrew and St. Peter. By the end of the 18th Century the population of the area was just over two and a half thousand, rising to around four thousand over the next fifty years. The church of St. Mary the Virgin in Ovingham was consecrated around the year 1050ad, being built on the site of an even earlier Christian meeting place marked by fragments of a cross. The early days of the church are quite evident in that it has Saxon, Norman, and early English architecture. The church records here date from 1679. Nearby Wylam lies 2 miles east of  Ovingham and was once rich in ironstone and colliery work. The engineer, George Stephenson was born here in 1781. The Wylam of Mary Cowper's time was a large wooded area with cottages spread around the parish and a waggonway heading towards the loading point at Lemington. The waggonway had opened in 1748 and ceased to operate in 1867. What Mary actually saw was horse drawn coal wagons on wooden tracks. The picture that follows is of the original cottage that George Stephenson was born in, which shows the style and structure of the era that Mary Cowper lived in as a child. This house is today a protected building.

Ovingham and was once rich in ironstone and colliery work. The engineer, George Stephenson was born here in 1781. The Wylam of Mary Cowper's time was a large wooded area with cottages spread around the parish and a waggonway heading towards the loading point at Lemington. The waggonway had opened in 1748 and ceased to operate in 1867. What Mary actually saw was horse drawn coal wagons on wooden tracks. The picture that follows is of the original cottage that George Stephenson was born in, which shows the style and structure of the era that Mary Cowper lived in as a child. This house is today a protected building.

Sources suggest the Cowper surname was possibly first located in Cumberland around the time of the Norman Conquest, where they held a family seat as Lords of the manor at Carleton Hall and Unthank. This hall, today serves as the headquarters for Cumbria Police and was listed as a Grade 2 building on 24th April 1951. The hall can be located on the A66 Penrith road. The motto on the Cowper coat of arms is Industria ET Perseverantia, which translated into plain English reads as By Industry and Perseverance. Since official marriage records were introduced, it has been found that up until 30th June 1837 a total of 1760 persons with the surname spelling of Cowper got married in England, with the largest hoard occurring in the County of Yorkshire, where a total of 606 marriages occurred. Cumberland, however, was eleventh on the list with only 47 marriages and Northumberland lay in twelfth place with only 43. In its own right, County Durham lay in seventh place with 69 entries. From these records, it is shown that the biggest strongholds for Cowper, lay not in Cumberland, but more southern, in Yorkshire and the Midlands.

The origin of the surname is Anglo Saxon deriving from the German word "Kuper" itself a derivative of "Kup" - or container. The name refers to the medieval craft of barrel and tub making, when a person of such skill was called a Cooper. The Cowper word was probably used in England in the 8 Century but in 1562, the name seems prominent in Ecclesfield, Yorkshire. The very first recorded spelling of the family name is thought to be that of Robert le Cupere, who in 1176 lived in Sussex, during the reign of King Henry the second. Surnames became necessary when governments introduced personal taxation. In England this was also referred to as Poll Tax.

One hundred years prior to the birth of Mary Cowper, her ancestor's had lived and worked in Corbridge until they moved to the Ovingham area in the 1680s. The former had quite a colourful history, once being a supply town for the troops on Hadrian's Wall. Over the centuries that followed the Roman rule, Corbridge was burned to the ground several times due to Border warfare, but, just like the Phoenix, the village rose from the fires of destruction and thrived over and over. Following the Tyne Valley Floodings of November 1771, the bridge at Corbridge was the only bridge on the Tyne to escape destruction. It was the oldest Mediaeval Bridge in existence, but had become derelict in the 1600s, being replaced in 1674. When the Cowper's lived there, Corbridge was mainly agricultural, of which evidence survives to date. However, the area was also rich in sandstone, iron, lead, and silver, the latter causing the creation of a mint at Corbridge and Carlisle. The main street in Corbridge was once known as Smithgate due to the vast number of iron working shops. The area had boasted a market, held since the days of King Henry the Second, although the Cowper's would not have seen much of this due to the market's decline in the early 1660s. Second in Grandeur, only to Newcastle, Corbridge was hit by the Black Death in the 14th Century and the town's prosperity declined considerably.

One hundred years prior to the birth of Mary Cowper, her ancestor's had lived and worked in Corbridge until they moved to the Ovingham area in the 1680s. The former had quite a colourful history, once being a supply town for the troops on Hadrian's Wall. Over the centuries that followed the Roman rule, Corbridge was burned to the ground several times due to Border warfare, but, just like the Phoenix, the village rose from the fires of destruction and thrived over and over. Following the Tyne Valley Floodings of November 1771, the bridge at Corbridge was the only bridge on the Tyne to escape destruction. It was the oldest Mediaeval Bridge in existence, but had become derelict in the 1600s, being replaced in 1674. When the Cowper's lived there, Corbridge was mainly agricultural, of which evidence survives to date. However, the area was also rich in sandstone, iron, lead, and silver, the latter causing the creation of a mint at Corbridge and Carlisle. The main street in Corbridge was once known as Smithgate due to the vast number of iron working shops. The area had boasted a market, held since the days of King Henry the Second, although the Cowper's would not have seen much of this due to the market's decline in the early 1660s. Second in Grandeur, only to Newcastle, Corbridge was hit by the Black Death in the 14th Century and the town's prosperity declined considerably.

Mary Cowper's father, John possibly died at Ovingham in 1769, burial records showing a certain John Cowper being buried in St. Mary's graveyard in that year. Mary herself came to County Durham around that time and settled in Brancepeth, 5 miles from Durham City. However, she was not the first Cowper to settle in Brancepeth, baptism records showing that Cowper's had resided here since at least the early 1600s. With that in mind, it is logical to suggest that Mary possibly came to live with relatives following her father's death. Cowper burials in Durham show on records as early as 1545, and at St. Brandon's, Brancepeth, as early as 1670 with the burial of one

Temerantia Cowper. A certain Anne and John Cowper were both buried in this churchyard in 1681 and 1682 respectively. Four marriages also show on the records of St. Brandon, although there were probably more due to the misspelling of the Cowper surname. Mary's own surname is often a misspelling, showing as Cooper, but the latter is incorrect. Upon her marriage to Peter Pearson in 1781 Mary adopted her husband's legal place of settlement, this being the law of the land, Peter himself must have underwent the process of Settlement when he came to live and work in Witton Gilbert from Butcher Race, as a joiner and woodman. It is known from records that he had been in Witton Gilbert since at least the 1st July 1776, when, as a villager, he witnessed the wedding of Jonathon Wintrop and Jane Kerring at St. Michael's Church. Any surviving Settlement Certificate would therefore be found dated between 1759 and 1776. Since 1691, the law had required that a person wishing to settle in another village had to give notice of 40 days, this being due to any complaints being made to the local Magistrate. A Settlement Certificate was either hand written or printed, and before 1733, was most likely written in Latin. It was issued by the Overseers or Churchwardens, so that the cost of issue and sending of a certificate for a named person may be recorded in overseer's accounts. Sometimes, the Overseer's kept lists of those arriving ‘by certificate’ in the parish, and early certificates usually contained less details on family members. No one was allowed to move from town to town without the appropriate documentation.

In the 18th Century the main village of Brancepeth was bounded on the north by Lanchester and Esh, on the west by Witton -le-wear, southwest by Crook, and to the south and south-east by Croxdale, Merrington, Whitworth, and St. Andrew's Auckland. In the late 1790s the population count of Brancepeth was quite small, around 360 persons, and did not really grown in size until the mid to late 1850s. On Sunday 25th November 1781, Mary and Peter married  at St. Brandon's Church in Brancepeth having undertaken marriage banns in both Brancepeth and Witton Gilbert. Mary was six months pregnant at this point, her first child being due the following February. The church that they viewed was different to the church we see today, mainly due to its reconstruction following a serious fire there in 1998. What Mary and Peter viewed was a beautifully carved wooden interior, sadly destroyed by the fire, reaching a temperature of 1200 degrees Celsius at its height.

at St. Brandon's Church in Brancepeth having undertaken marriage banns in both Brancepeth and Witton Gilbert. Mary was six months pregnant at this point, her first child being due the following February. The church that they viewed was different to the church we see today, mainly due to its reconstruction following a serious fire there in 1998. What Mary and Peter viewed was a beautifully carved wooden interior, sadly destroyed by the fire, reaching a temperature of 1200 degrees Celsius at its height.

Right – St, Brandon's Church in Brancepeth, County Durham where Mary Cowper and Peter Pearson

The church of St.Brandon dates from the 12th Century and stands in the  shadow of Brancepeth Castle - home for many centuries of the noted

shadow of Brancepeth Castle - home for many centuries of the noted

Neville Family. There was a historical plus to come out of the fire damage though, as more than a thousand Medieval gravestones were found stored in the walls of the church, laid their hundreds of years previous. The Brancepeth that Mary Cowper viewed in the late 1770s was not very dissimilar to what we see today. The area was agricultural with farms spread here and there, and near Brancepeth Castle, a row of houses had been freshly built, that today still holds that unique rural charm. The Colliery was not to appear for another 60 years, when in 1840, the sinking had begun at Byers Green. Of course, with the Colliery, the population of Brancepeth inevitably increased.

Right – Brancepeth Castle, where St Brandon's Church lies in its shadow

In Witton Gilbert, Mary and Peter are thought to have lived in a dwelling near the Fold at the eastern end of the front street. The Fold was once the site of a market, and during Peter's time, rural produce was sold here. At the opposite end of the main street was a busy turnpike road leading towards Norburn Lane. Peter's earnings as a joiner meant that Mary did not have to work; instead she kept the house in an orderly fashion while Peter brought home the money, by working for the people of Witton Village and probably selling his wares at Durham Market. Their first child, Eleanor Pearson was born at Witton Gilbert in 1782, being baptised on 21st February that year at St. Michael's. Mary's life now took a new path - as well as housekeeper, she now became a full time mother. This bond between mother and child was to end, when, sadly, Eleanor died in 1789 at the age of seven. Two years previous to this, Mary had the sorrowful task of attending the funeral of her two years old daughter Jane Pearson who had died in February 1787. Funerals, in those days consisted of garlands of flowers being hung in the church, fastened to loops in which were slips of paper bearing the names of the deceased. This practise in St. Michael's was common until it ceased in 1873. Mary mothered seven children in total, five daughters and two sons, all born in the village between 1782 and 1797.

The 1790s were a worrying time for Witton Gilbert, with the new threat of war looming on the horizon, mainly coming from the French. Church records indicate a meeting taking place at Witton Gilbert church hall on the evening of Tuesday 3 rd April 1798 of which Peter attended. We know this due to his signature, in thick black ink appearing on the records. Mary most likely stayed at home on that evening, tending to her six children. Had the war escalated, undoubtedly, Mary's sons, John and Peter would surely have received service papers. Gladly, this did not happen, as the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte were halted at Trafalgar in 1805. A French Priest was buried at St. Michael's in 1797, having fled from France, during the Revolution. He was making his way to Ushaw when he took ill at Findon Cottage and died.

Life in Witton Gilbert in Mary's time there was abrupt. Manners, speech, and customs were course. Popular sports at that time were bear-baiting, bull-baiting, and cock-fighting. Executions, which took place at Dryburn often served as an excuse for a public holiday. To picture how Mary lived, one must first of all understand what was happening in the village. The collieries were not to appear near here until the late 1830s, and at the end of the 18th Century, the village, although course; still had a very rural feel with the majority of the inhabitants engaged in agricultural pursuits. The village itself was of some importance, as it was a convenient meeting place for traders from the west of the county to meet traders from the east. Farmers from the Dales brought wool and livestock to trade for coal brought by the men from the east. The village, on market day was extremely hectic, and two markets in total were used for the exchanges. Not forgetting, Mary and Peter lived right next to the Fold, which meant going about their usual daily outdoor tasks on market day, was practically impossible. The other market in use was set up in a field near the Norburn Lane toll gate. At one point, the village made money by erecting two toll gates.

However, Mary adapted to this way of life well, both Peter and herself becoming respected members of the community. The church played an important role in their lives, and indeed, in the years that followed, their grandson, Peter Pearson (1823 -1907) was for 46 years until his death, the Rector's Churchwarden at St. Michael's. The latter's own skill in joinery and carpentry was learned from his grandfather until the latter's own death in 1841. Mary's first born son, John was baptised on 26th December 1784, and had wed in 1809. In that year, Mary welcomed her first grandchild, Robert Pearson, and many more grandchildren were to follow, about twenty-one in total. Her love for these grandchildren would never disguise the sadness she felt by the loss of her own children, and in January 1816, the curse struck once more with the death of Eleanor, Mary's second youngest child. Eleanor, or Ellen as she preferred was born in 1794 and had been named out of respect to her older sister who had died in 1789. In 1814 she had married Thomas Jacketts, a marriage which had produced one child, John. Soon after the birth of John, Ellen had taken ill and died aged just 22. If that wasn't bad enough, the child died the following January in 1817, aged a year old. Mary, for all her strength of mind must have been absolutely heartbroken. Taking into account the deaths of Mary's children and grandchildren, including the unnamed ones, a pattern emerges; that being the majority of the deaths occurred in the months of January and February, which ultimately suggests cold winters and bad harvests. One feels that in the case of the children, pneumonia may have actually been the culprit, but medical expertise being what it was back then, may just have put it down to natural causes.

As the years advanced, Mary's own life had to adapt to the changes that were to come. By the late 1830s, the village and its surrounds had changed from a rural setting to one of a noise ridden, working area. The Industrial Revolution had arrived and with it came the population rise. Suddenly, Witton Gilbert was inhabited with strangers who had come to work in the local coal mines at Sacriston.

As the years advanced, Mary's own life had to adapt to the changes that were to come. By the late 1830s, the village and its surrounds had changed from a rural setting to one of a noise ridden, working area. The Industrial Revolution had arrived and with it came the population rise. Suddenly, Witton Gilbert was inhabited with strangers who had come to work in the local coal mines at Sacriston.

Mary had just turned 81 when her health took a turn for the worst. She had always been a strong woman, but as the saying goes - "we are born to die". Her death certificate would suggest that her family were with her when she passed away on 15th March 1841. She was laid to rest in the churchyard of St. Michael's, followed eight months later by her devoted husband Peter. Their grave lies to the left of the church itself and is the final resting place of Mary, Peter, and their daughter Ellen.

Via the use of Census Returns and Ordinance Survey Maps, it is believed that Mary died at these premises

(green door) possibly another building that occupied this space on 15th March 1841.